The professional world of modern legal services is essentially unanimous in concluding that analytic skills, which law schools focus on (particularly in US-style JD programs), are only parts of what makes lawyers successful.

What are the other skills? Competencies of different sorts. But once we get past elementary matters of substantive legal knowledge; ethical conduct; and perhaps rudimentary law office management, there is less agreement on which competencies matter or matter most. And there is almost no agreement as to how lawyers (especially law students and new lawyers) are supposed to find and acquire them.

Should law schools implement programs to instill additional (or different competencies) in law students? Should law firms and other professional organizations train and support their new hires as part of the professional development? Should third parties innovate in the gaps between legal education and professional development? Should students and new lawyers search out new and different modes of training? All of these?

The competencies are, helpfully, bundled, making the how questions a bit easier to answer, in principle. They’re bundled in models: models of the successful lawyer. Models that have shapes and letters.

Still, it’s not always clear who is supposed to use the models. They are mostly promoted by and/or for practicing lawyers and legal services organizations. Law students, beginning lawyers, and law schools are largely left to fend for themselves, although if you read to the end of the list below, you’ll see some important exceptions to that statement. There is convergence between the services world(s) and the education and training world(s) in the future, I suspect (or hope), though it is not easy to see what that convergence looks like.

(Also, one hopes that space remains for exploring when and why we should not treat human beings as (metaphorically) inanimate objects, or concepts.)

For a start, I thought that it would be useful to collect the models in a single place. Here is a list:

The T shaped lawyer

The intuition behind the “T shaped” model is simple. The vertical line represents depth of expertise (the “I shaped” model of performance), usually substance of the law and related “legal” skills. The top, horizontal bar (the “Dash” model) represents breadth of ability touching on additional disciplines and skills, beyond law itself.

The initial elaboration of the T shaped idea in law is credited to Amani Smathers, in this relatively recent short article.

Today, the “additional skills” vary, depending on who is promoting the T. One finds (among other things) finance, project management, collaboration, emotional intelligence, technology, data analytics, design.

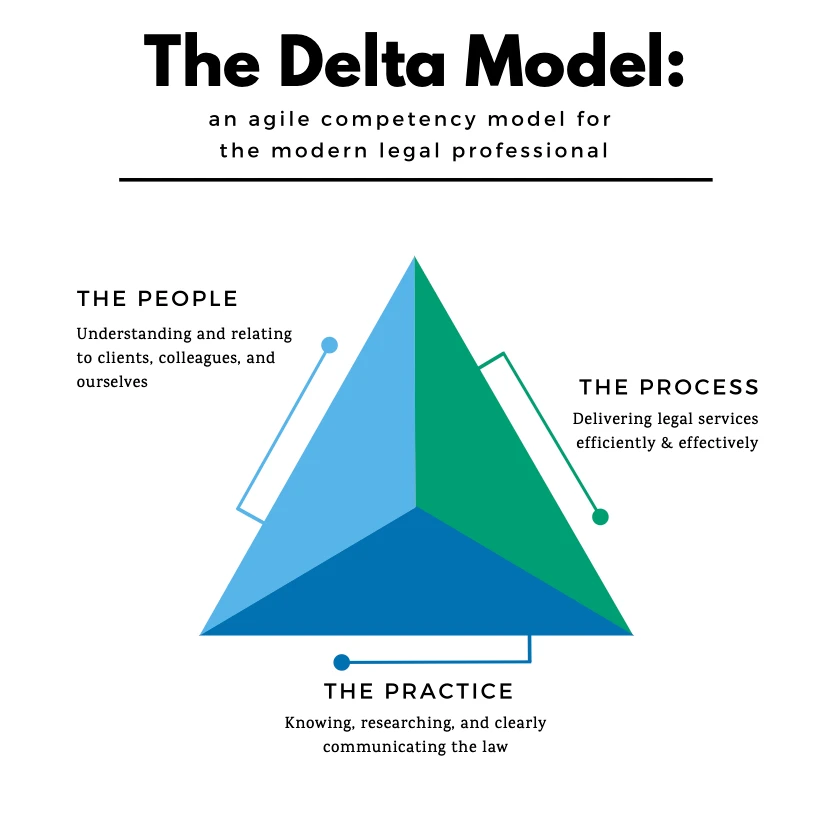

The Delta Lawyer Competency Model

A group of US law professors (and a colleague at Thomson Reuters) has taken the T-shaped model and elaborated it in something they call the Delta Model of lawyer competency.

The intuition is again relatively straightforward. The “delta” in the model is an equilateral triangle, and the space inside the model is divided into three equal parts. Each part represents an opportunity for the individual lawyer to develop a cluster of related competencies, now bundled in three groups: “the law” [practice-related]; “personal effectiveness” [people-related]; and “business and operations” [process-related].

The labels are less significant than the competencies that they signify. That’s partly because the “Delta Model Working Group” continues to refine the model to turn it into a useful assessment instrument for both trainers (organizations, mentors) and trainees (students and new lawyers). And it’s partly because the Delta Model is conceived as an adaptable and dynamic tool. Unlike the T shaped model, which can give the impression of dictating a single standard for success across all professional fields, the competency-specific priorities of the Delta Model can be tailored by setting and even by individual professional.

The development of the Delta Model is summarized here, again at Legal Evolution.

The team has a home for the model here, at Design Your Delta.

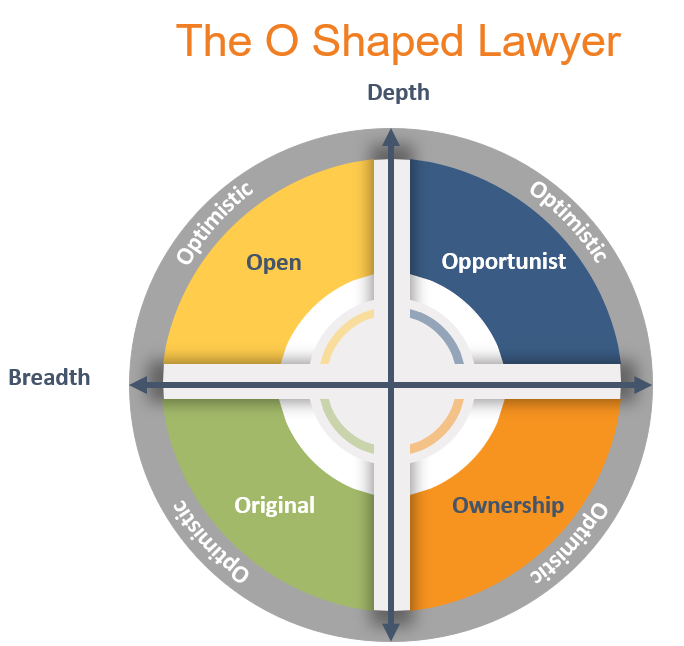

The O Shaped Lawyer

The shape of the successful modern lawyer isn’t a puzzle only in the US, which surprises no one. In the UK, a group of general counsels have advanced what they call the “O shaped” initiative.

The “O” shape is meant to communicate the general idea that modern lawyers should be “well-rounded,” and the specific ideas that they should be trained to be Optimistic about their power to find solutions; to take Ownership of outcomes; to be Open-minded about possibility (the growth mindset); Opportunistic in the face of risk; and Original (a synonym for creative).

Perhaps because the initiative Originates in the business world rather than in the private law firm world, it comes colored with some marketing punch. The initiative has a home page here.

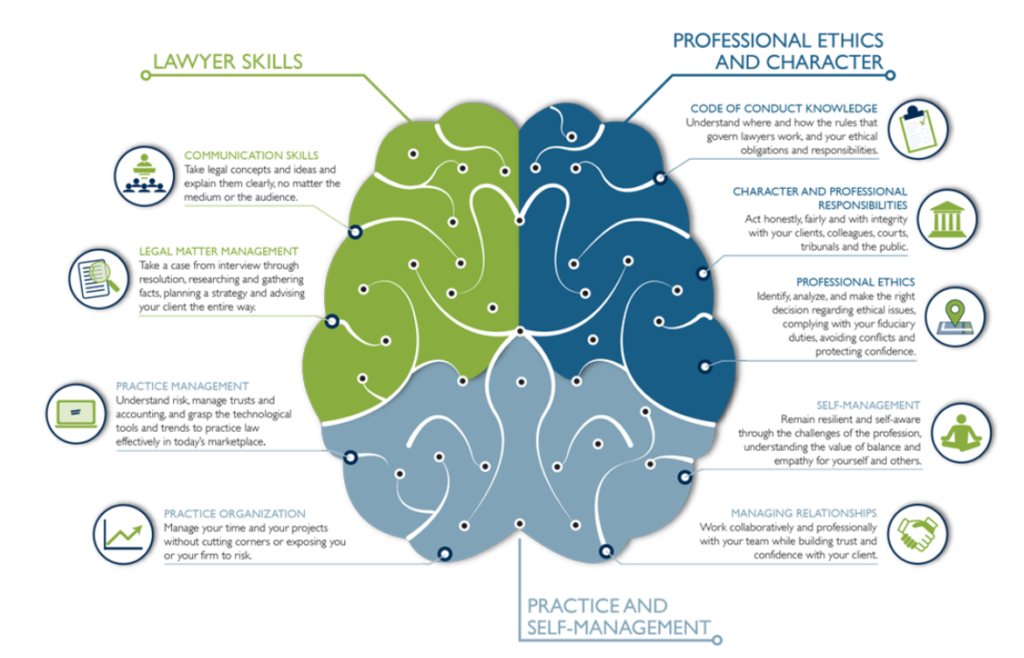

The CPLED Competency Framework

The Canadian Centre for Professional Legal Education (CPLED) have developed a competencies model (they call it a framework) that is used in connection with preparing new law graduates for licensure in four Canadian provinces: Alberta, Manitoba, Nova Scotia and Saskatchewan.

Like the Delta Model, the CPLED framework groups competencies into three bundles: lawyer skills, professional ethics and character, and practice and self-management.

Unsurprisingly, given the origins of the framework in an organization that focuses on preparing new graduates to be called to the bar (to use the Canadian phrase), these groups and their subsidiary elements are each more closely tied to the traditional identity and professional practice of the lawyer than the multi-disciplinary approach offered in the T shaped model.

The CPLED Competency Framework is described here.

The Whole Lawyer

Some of these efforts, but not all of them, evoke early 21st century initiatives to promote teaching “the whole lawyer,” as an expression of legal education’s then newly-discovered interest in promoting “identity formation” as a critical pillar of legal training.

“Professional identity” captured three inter-related ideas: the lawyer’s ethical duties as matters of professional obligation; practices of ethical self-care and moral judgment in the life of the lawyer; and the lawyer’s awareness of the broader social contexts in which the lawyer functions. The so-called Carnegie Report of 2007 substantially advanced the idea of an “apprenticeship” for new lawyers in the “professional identity” domain, but on its own the Report did not propose a model of competency-based identity.

Perhaps the best adaptation of the spirit of the Carnegie Report into something metaphorically concrete and actionable by students (if not by firms and other legal services employers) is Neil Hamilton’s excellent book titled Roadmap: The Law Student’s Guide to Meaningful Employment.

Alphabet Soup: Of M-shaped, X-shaped, Pi-shaped, and Comb-shaped People

As models of lawyers’ performance proliferate, pathways to professional success may get more more confusing rather than less so. A similar impulse in the management literature appears to have claimed a good part of the alphanumeric world, creating what might appear to be a shopping mall of models from which to pick and choose.

(One wonders whether what the proliferation of models signifies over the longer term.)

The “M shaped” and “Comb shaped” performers are people with depth of expertise in more than one identified fields or disciplines and the skills to collaborate across those domains. A Pi shaped person combines M and T shaped competencies. It is said that they are cross-functional, collaborative, and, because of their T shaped breadth, adaptive.

The Shultz & Zedeck Lawyer Effectiveness Factors

This list of competency models would be incomplete without reference to the foundational research of Marjorie Shultz and Sheldon Zedeck on factors that contribute to lawyers’ effectiveness in practice, Identification, Development, and Validation of Predictors for Successful Lawyering (2009). Their work was produced with support from the Law School Admission Council (LSAC), based on the intuition that predictors of professional effectiveness might be combined productively with predictors of academic success when law schools make admissions decisions. The Shultz and Zedeck research described 26 factors that, assessed against an individual lawyer’s performance, predicted the effectiveness of a practitioner.

The IAALS Foundations project

Last but by no means least, the Institute for the Advancement of the American Legal System (IAALS), formerly the parent of the Educating Tomorrow’s Lawyers initiative, conducted an immense study of practicing lawyers to determine, as IAALS puts it, (i) the foundations entry-level lawyers need to succeed in the practice of law, (ii) measurable models of legal education that support those foundations, and (iii) ways to align market needs with hiring practices to incentivize positive improvements.

The results of this work are known as the Foundations for Practice materials. Foundations for Practice offers less a model of the practicing professional and more a checklist of competencies that graduating students and beginning lawyers should master in order to find a job (by meeting employer expectations on day 1) and begin their careers in practice. IAALS is continuing the work of developing proposed curricular materials to translate the research results into programmatic changes in US law schools.

The Unknown: Empirical Evidence of Attorney Impact

External measures of lawyers’ success and impact (as opposed to internal measures suggested by the lawyer-reported data collected by Shultz and Zedeck, and by the IAALS team) are difficult to come by. Selection effects are significant; it can be difficult to observe the impact of individual lawyers within team-based contexts. One study that attempted to measure and define effective lawyering is David S. Abrams & Albert H. Yoon, “The Luck of the Draw: Using Random Case Assignment to Investigate Attorney Ability,” University of Chicago Law Review (2007, available at chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclrev/vol74/iss4/1.