The Terrible Towel trademark is on the move again.

The Terrible Towel is a Pittsburgh Steelers tradition. It’s a piece of cheap yellow (or gold) terrycloth emblazoned with a “Terrible Towel” (TT) logo; Steelers fans twirl the towels by the thousands whenever and wherever the team plays.

Earlier this year, when the owner of the TT mark sent a cease and desist letter to an alleged infringer, I wrote this post about possible problems with the validity of the TT mark. The mark strikes me as a classic example of marks as merchandise, or what trademark lawyers sometimes refer to as the “Boston Hockey” problem, after an old case from the Fifth Circuit.

Another TT trademark claim has popped up in the news, and now I have a different question about the mark.

The claim in this news is this:

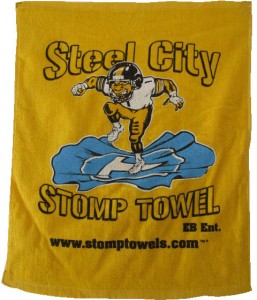

One Eugene Berry, a young entrepreneur in the Pittsburgh area, recently expanded his business to include an application for a trademark registration for something called the “Terrible T-Shirt,” pictured at left. Previously, Berry had been producing and selling something called the “Stomp Towel.” The original Stomp Towel was a novelty item, a piece of terrycloth with “Stomp Towel” painted on it, along with a “Steel City” logo and an image of a Pittsburgh Steelers football player stomping on a blue towel. The Stomp Towel and its iconography are traceable to an incident at a Steelers/Tennessee Titans game in 2008, at which a Titans player stomped on a Terrible Towel to indicate his disrespect for the Steelers team. The Titans wear blue and white uniforms. Stomp Towels are now being produced with colors and iconography related to several NFL teams, but the Stomp Towel is, apparently, not at issue in the new case. (You can buy Stomp Towels here.) The Steelers have sued Eugene Berry over the t-shirts.

One Eugene Berry, a young entrepreneur in the Pittsburgh area, recently expanded his business to include an application for a trademark registration for something called the “Terrible T-Shirt,” pictured at left. Previously, Berry had been producing and selling something called the “Stomp Towel.” The original Stomp Towel was a novelty item, a piece of terrycloth with “Stomp Towel” painted on it, along with a “Steel City” logo and an image of a Pittsburgh Steelers football player stomping on a blue towel. The Stomp Towel and its iconography are traceable to an incident at a Steelers/Tennessee Titans game in 2008, at which a Titans player stomped on a Terrible Towel to indicate his disrespect for the Steelers team. The Titans wear blue and white uniforms. Stomp Towels are now being produced with colors and iconography related to several NFL teams, but the Stomp Towel is, apparently, not at issue in the new case. (You can buy Stomp Towels here.) The Steelers have sued Eugene Berry over the t-shirts.

Well, of course, it’s not just the Steelers who have sued. The TT mark itself is owned by the Allegheny Valley School (AVS), for historical reasons that I reviewed in my earlier post, and the AVS is a named plaintiff. But the Steelers are a plaintiff (sorry about the syntax there); the Steelers allege that they are the exclusive licensee of the mark. The plaintiffs allege that “the marks have become widely recognized by the general consuming public of the [U.S.] as a designation of source of the goods, thus earning the status of a famous mark.” How has this happened? According to the complaint, over the 30+ years of production and use of TTs, the goods have become widely associated by consumers with the Steelers football team.

Well, of course, it’s not just the Steelers who have sued. The TT mark itself is owned by the Allegheny Valley School (AVS), for historical reasons that I reviewed in my earlier post, and the AVS is a named plaintiff. But the Steelers are a plaintiff (sorry about the syntax there); the Steelers allege that they are the exclusive licensee of the mark. The plaintiffs allege that “the marks have become widely recognized by the general consuming public of the [U.S.] as a designation of source of the goods, thus earning the status of a famous mark.” How has this happened? According to the complaint, over the 30+ years of production and use of TTs, the goods have become widely associated by consumers with the Steelers football team.

Well.

I understand that a valid mark requires only that the consuming public recognize the mark as an indicator of source. The public need not recognize or even know *who* or *what* the source is; the public need only look at the mark (or hear the mark, etc.) and think, in some collective sense, “that mark tells me that all stuff bearing that mark is traceable to the same source. I have no idea what that source is.” The Golden Arches is a valid mark; every time the public sees the Golden Arches at a restaurant or on a package, the public has learned to infer that all burgers, shakes, and fries at that restaurant are traceable to a common source.

The problem, as I see it, is that it is commonly assumed that the source in question — even if the source is unknown — is in fact the owner of the mark. I may not know that the Golden Arches mark is owned by McDonald’s Corporation, but in fact the Golden Arches mark *is* owned by the McDonald’s Corporation. The architecture of trademark law and business depends on that fact: McDonald’s was the first user of the mark in commerce; McDonald’s owns nationwide rights in the mark and controls the goodwill associated with the mark; McDonald’s licenses the mark to franchisees and embeds that licensing program in a rich context of quality control in order to manage and maintain that goodwill. Consumers get a consistent product experience when they eat at a McDonald’s restaurant, even though McDonald’s Corporation does not actually produce the food, thus fulfilling one of the key policy goals of trademark law, and the validity of the Golden Arches mark is preserved against a possible claim of “naked licensing.” Consumers do not associate the goodwill signified by the Golden Arches mark with the owner of a particular McDonald’s restaurant. If they did, then ownership of the mark would be in the hands of one enterprise (McDonald’s Corporation) and the goodwill associated with the mark would be in the hands of someone else (the local franchisee). “Naked licensing” would rear its head, and the mark might well be invalidated.

Or so I have always assumed.

The Steelers’ allegation in the current complaint raises a different possible interpretation of trademark law. The alternative interpretation goes like this: Consumers associate with mark with a particular source, and that is all that the statute requires. The fact that the source, in consumers’ minds, turns out to be a licensee (the Steelers) of the mark owner (the AVS) is irrelevant in the statutory scheme. Mapping the claim back to my McDonalds’ example: the fact that consumers associate the goodwill signified by the mark with the local franchisee is irrelevant to the mark’s validity, even if the mark is owned and controlled by the franchisor, if consumers consistently associate that goodwill with that franchisee.Â

“Naked licensing” is a problem for trademark law because it leads to the legal inference that the mark has been abandoned. That is, the mark owner has not exercised the degree of control over quality of the goods or services associated with mark to ensure that consumers get what they think they are getting. The owner of the mark is not using the mark to signify source in the minds of consumers.

Ordinarily, naked licensing is entirely avoidable if the mark owner has good trademark counsel. A well-structured trademark license will preserve for the mark owner the right to control the quality of the goods produced under the license and to monitor that quality. That’s not much of a burden to bear. Naked licensing can also be avoided if the mark owner exercises actual control over quality of the goods, or if (as the Ninth Circuit noted in the recent Freecycle case) the mark owner reasonably relies on quality control provided by the licensee, because, usually, the licensor and licensee have a long-standing and close business relationship. I don’t know the terms of the Steelers/AVS license. I do know that the Steelers (and AVS) have excellent trademark counsel.

But in this case does even a well-drafted license solve the underlying problem — which the plaintiffs in the case don’t simply acknowledge, but affirmatively allege — that consumers associate the mark with the licensee rather than with the mark owner? Or is my inherited sense of trademark architecture off base? Maybe there isn’t a problem here at all. Thoughts?

Of course, if there is a problem, there’s a solution, though it is not simple: the AVS could assign its rights in the mark to the Steelers, as part of a deal by which the Steelers promise to convey profits from the mark back to AVS (thus fulfilling Myron Cope’s original goal — see my prior post). That’s not an uncomplicated solution, because there would be a significant risk that the Steelers’ priority in the mark would date from the date of the deal, rather than from some date in the past (say, the original priority date of AVS’s alleged use of the mark).

Supplemented, Aug. 30:

Considering Megan Carpenter’s comment below and some additional conversations with trademark experts, I am persuaded that my speculation above is a bit off the mark. That leaves me with some additional questions, though.  It may be the case that the AVS and the Pittsburgh Steelers have threaded the eye of the Lanham Act needle.  The trademark scheme still leaves me scratching my head.

The Lanham Act provides, in connection with registration, that use of a mark by a “related” company “inures to the benefit” of the mark owner (registrant). That’s the basis for the standard version of my McDonald’s example above. Use of the Golden Arches by a McDonald’s franchisee “inures to the benefit” of McDonald’s Corporation, because the companies are “related.” “Related” means, in context, that there is some contractual or other relationship that ensures that consumers are not deceived about the quality of the goods and services delivered under the marks. That continues to be true even if consumers have no idea about the identity or even the existence of McDonald’s Corporation, and even if they associate with quality of their Quarter Pounders with the neighborhood McDonald’s store. The public policy behind the “inurement” rule closely parallels the public policy behind the “naked licensing” rule: so long as consumers get a consistent product/service experience associated with the mark, then consumers are not deceived. The mark is valid; actual ownership of the mark is, for this purpose, not relevant.

In short, when I wondered above about the validity of the Terrible Towel mark if consumers believe that the TT comes from the Steelers rather than from the mark owner, the AVS, there may be a statutory basis for confirming that the mark is valid and validly owned by the AVS. Why? If the AVS and the Steelers have a licensing relationship that in fact grants the AVS the power to monitor and control the quality of goods produced under the TT mark, then the consumer goodwill associated with the TT inures to the benefit of the AVS.

The head-scratching part of the problem is this. The inurement rule, like the quality control defense to a charge of naked licensing, relies on a legal fiction. So long as the mark owner implements a legal relationship with its licensee that creates “quality control” monitoring, then the law presumes that the character of consumer goodwill is unchanged, and benefits the owner. What if the facts on the ground show that consumers in fact associate the mark with the licensee as source of the relevant goods or services?

For an example, go back to McDonald’s. It seems to me that the inurement rule relies in a deeply implicit way on the logical assumption that consumers believe (subconsciously, perhaps) that all burgers and fries from all stores with McDonald’s marks are in some unknown way managed or controlled by a higher central power. Consumers may have no idea what or where that central power is, but consumers do not believe that it is a miraculous coincidence that Big Macs in Peoria look and taste just like Big Macs in San Diego. If, contrary to all of the evidence, consumers *did* believe that this was a miraculous coincidence — even though the parent company *does* monitor and control quality – then the logic of trademark law — that consumer association is the foundation of all valid marks — dictates that the McDonald’s marks should be invalidated. Or at least that each local store’s marks should be evaluated independently for priority and use.

Yet the inurement doctrine and the “quality control” defense to a charge of naked licensing may prevent that outcome. Do they? Do they create an irrebuttable presumption in favor of mark ownership and validity, so long as the “related” company and/or “quality control” provisions are satisfied?Â

In other words, the AVS/Steelers “Terrible Towel” situation still bothers me. Trademark doctrine might suggest that the AVS/Steelers license agreement inoculates the TT mark against a charge of naked licensing, even though consumers *actually* associate the TT mark with the Steelers. In other words, the TT case may not be one in which consumers have *a* source association, but do not know what that source is. That would be the real world McDonald’s case. Instead, the TT case may be my imaginary McDonald’s case, one in which consumers have a source association, and that source association consists of actual — but mistaken — knowledge of the identity of the producer of both the mark and the products. Â

In that world, I am assured, trademark law poses no barriers to enforcement of the mark. That is, in a world in which the licensor (mark owner) has not engaged in naked licensing, because appropriate licensing and quality control measures are in place, but the consuming public truly but mistakenly believes that the mark and related products are associated exclusively with the licensee, then the mark remains valid, and ownership lies with the licensor.

I understand the commercial logic of this.  I also think that it does some more than minor violence to the consumer-protective dimensions of trademark.

With the caveat that my brain is foggy due to an attempt to cut down on my consumption of caffeine (and the disclaimer that I am a Steelers fan): You raise some interesting questions. Assuming proper quality control in the licensing provisions, I don’t know that there is a problem with a plaintiff licensee’s allegation that the relevant consumers associate the mark with the licensee. A university start-up is a good example: If researchers at University X create a start-up that is then spun-off, sometimes X will retain IP, including ownership of the marks, but license the rights to those marks to the company. Often, the consuming public will remain unaware of X’s involvement, and simply associate the marks with the licensee. It’s an interesting question when it comes to otherwise unrelated entities, (like the Steelers and AVS), but I’m not sure that makes a difference from a trademark perspective. Perfect timing for the start of football season, either way!

Comments are closed.