As Ann reports below, Mark Lemley and Mark McKenna are sharing a new paper on the overbreadth of “likelihood of confusion” analysis in contemporary trademark law. These thesis of the paper seems incontrovertible to me, but the paper frames its argument with an initial anecdote that bears a little exploration. They write:

In 2006, thousands of soccer fans showed up to the World Cup game between the Netherlands and the Ivory Coast wearing pants in the colors of the Dutch national team. The pants had been given out as promotional gifts by a beer company. FIFA, the governing body of international soccer, objected. It owned the trademarks for the team colors, and giving out pants in those colors was in FIFA’s view “ambush marketing†that was likely to confuse those who saw (or even those who wore) the pants into thinking that the soccer team had sponsored the pants. And in FIFA’s view, not only was giving out the pants illegal, but individuals wearing them were falsely suggesting some affiliation with the Dutch national team. Prohibited from wearing the pants into the stadium, more than one thousand fans dutifully took their pants off and cheered the Dutch team to victory in their underwear.

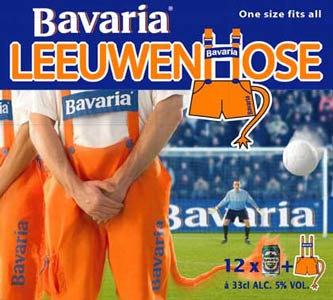

This is all correct, but there is both more (and perhaps less) to the story than meets the eye. Here is an image of the ad campaign developed by Bavaria, the Dutch brewer that supplied the pants:

What’s missing from the paper’s initial account is the fact that the beer company’s name appeared prominently on the pants (lederhosen, in fact, or what Bavaria called “leeuwenhose,” playing on the fact that the leeuwen, or lion, is a national symbol of the Netherlands. Note the “tail” at the back of each pair. Also missing is the fact that the distribution of the outfits was part of an advertising campaign orchestrated by Bavaria to take advantage of the exposure that the Dutch team earned during the World Cup finals, and that FIFA, sponsor of the finals, had an exclusive sponsorship deal in place with Anheuser Busch. Bud was the suds of the Cup (which is ironic, of course, since at the time Bud was an American company sponsoring a tournament being played in Germany); Bavaria was not so subtly horning in on the action.

In fact, FIFA has an active campaign to guard against what’s called “ambush marketing”; in anticipation of next year’s finals in South Africa, FIFA has already begun to clamp down on unauthorized commercial use of the phrase “World Cup 2010” and equivalents.

Should any of this matter? In standard trademark terms, perhaps not; that’s a main point of the paper. FIFA has no business “protecting” consumers from arguable confusion about whether or not Bavaria was an official sponsor of the Dutch side. It strikes me as likely that people bought the pants because wearing orange to games featuring the national team is what the Dutch do. Hup, Holland, Hup, as they say! (In fact, apparently the Dutch fans who were forced to strip down revealed that they were, on the whole, wearing orange underwear.)Â

But it’s more than plausible that FIFA has a legitimate interest in protecting the exclusivity of the tournament sponsorship purchased by Anheuser Busch. The “pantsing” of the Dutch had little or nothing to do with consumer protection or likelihood of confusion, as such; this was a question of unfair competition. The problem here may be not that FIFA doesn’t have a claim, but that trademark law is a poor fit for the alleged harm.

And the remedy, of course, is something else entirely. The Dutch seemed to take the pantsing in stride. Perhaps, instead, the managers of Bavaria beer should have been forced to drink Budweiser.

Mike – thanks for the additional information. Very interesting. Regarding the conclusion that FIFA has a legitimate interest in its exclusive arrangement with Anheuser-Busch, the ability to enter such arrangements is itself an artifact of TM law. So it’s not clear to me why the fact that TM law could create exclusive markets that can be exploited should mean they get the right to prevent anyone else from using the national team’s colors for their ads. It’s kind of a circular claim.

Mark,

I’m not sure that it’s circular. AB’s interest lies in its trademarks, but only because trademark law happens to be the legal doctrine that companies swing about when they turn their brands into commodities. Cf. the merchandising cases, in which the plaintiffs may have a point, but not a trademark-based point.

The interest that AB wants to protect here (and that FIFA enforced) isn’t a confusion-based interest, or at least not the kind of classic consumer-focused confusion-based interest that you and Mark are talking about and — I should be quick to add — that I agree lies at the heart of trademark law properly conceived.

So, it might be wise to separate the question of the legitimacy of FIFA’s position in enforcing an exclusive licensing deal from the question of the legal doctrine that creates the licensed interest.

I can imagine an alternative business/legal world in which the agreement between AB and FIFA is neither grounded in trademark law nor gives either party standing to enforce trademark rights — yet each party has standing to pursue “ordinary” tort claims (unfair competition and interference with business advantage, for example) against third parties.

Of course, modern American trademark law calls that “dilution,” the difference being that “dilution” is trivially easy to plead, if not always to prove, compared to the standard requirements for its tort cousins.

I particularly like the last line, but it leads to a question that only those in Europe — or who obsess excessively about trademark law — will really understand:

Which Budweiser? Or should it be a blind taste-test to be admitted at trial in that trademark dispute?

Clever, but I think that the answer is obvious: The Bud that sponsored the 2006 World Cup, which as all Americans know is the King of Beers.

Comments are closed.